somebody’s baby

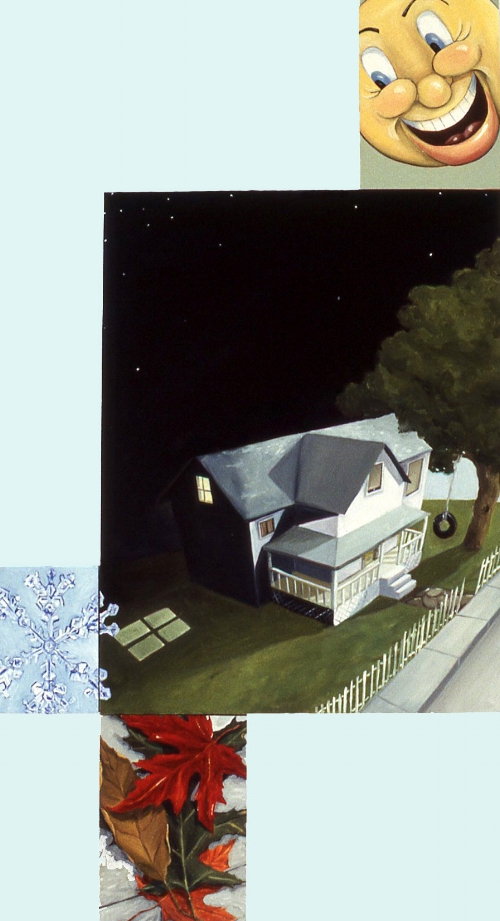

Every parent knows this: we change the moment our child is born. Becoming stronger than we thought possible---we are also far more vulnerable. We fear that our children will carelessly play their way into injury. Or perhaps a tragic twist of circumstances will truncate their potential. One of our most chilling fears even has a name: Stranger Danger - that our child will fall victim to the machinations of some isolated sociopath.

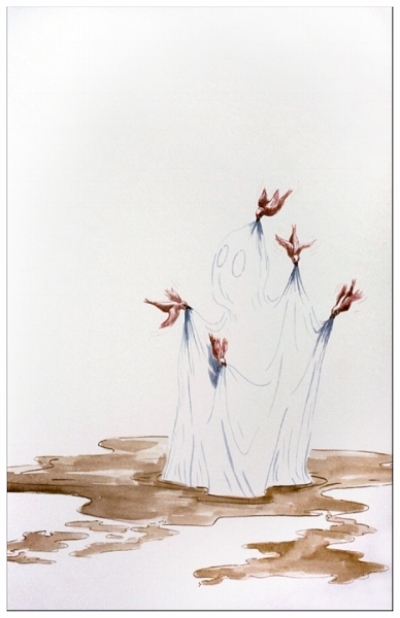

But what we don’t imagine is that our children will suffer and perhaps die alone, confused and terrified, systemically victimized by the services ostensibly designed to protect them. And yet, it happens; at this moment, there are approximately 1,800 Canadians inmates in solitary confinement, some as young as twelve years old. The practice is proven to cause severe long-term psychiatric trauma. Paradoxically, undiagnosed or under-treated mental health disorders frequently underlie the incident that lead to initial incarceration.

The link between psychiatric challenges, institutional abuse and the penal system is a slippery and well-worn slope - one with which our family has some experience. Our daughter’s struggle with multiple neurological disabilities has cast shadows over many of the silly joys of childhood, the darkest resulting from misinformed and punitive responses to moments of mental health crisis. Our daughter’s experiences have also revealed a core of brave resilience, insight and love. But while we look forward to building on these strengths as we guide her into adulthood, many families are not nearly as fortunate.

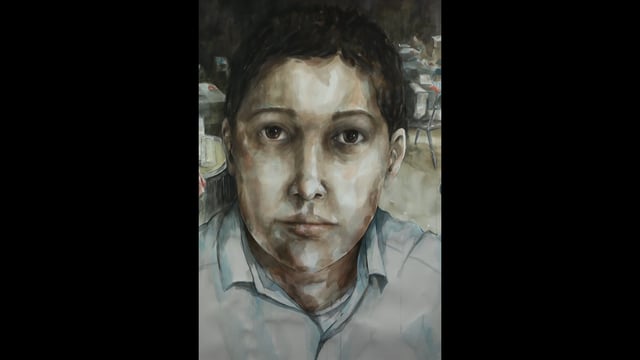

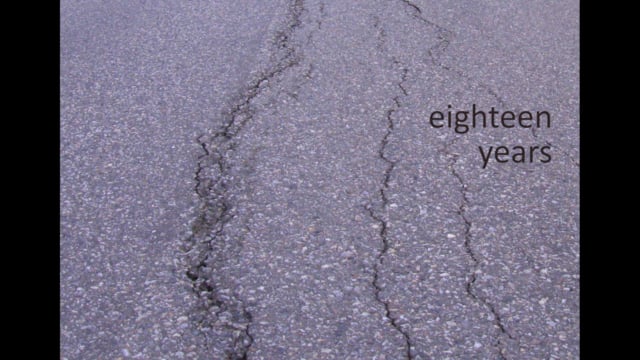

By all accounts, Ashley Smith shared many of our daughter’s qualities. Yet in 2007, nineteen year old Smith died at the Grand Valley Institute for Women in Kitchener, Ontario. At that point, she had been in continuous solitary confinement for almost a year. Over her brief lifetime, more than 1000 days were spent in segregation in federal and youth custody.

During the lengthy inquest into her death (2009-2013), many media outlets broadcast sensationalized imagery from her institutional abuse, including footage of her death, which correctional officers observed and recorded, yet did not intervene. Although this documentation ultimately served as persuasive evidence that lead to a verdict of homicide, its exceptionally graphic nature also tended to reinforce the illusion that horrific things only happen to vilified others. (In 2012, after viewing the footage, then Prime Minister Stephen Harper vowed to make changes to Corrections Canada’s methods, but nothing was done. Hopes have been cautiously raised with the election of Justin Trudeau, who has tasked Justice Minister Jody Wilson-Raybould with implementing the recommendations of the inquest.)

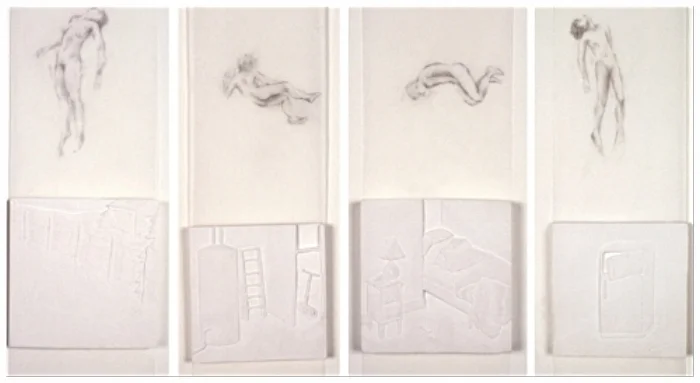

somebody’s baby is a reflection on the speed with which a mental health crisis may descend into criminalization and incarceration. When we discover the relative innocence of Ashley Smith’s initial infraction, throwing crab apples at a postal worker, we realize how easy it is to blame the victim.

As I began researching and discussing this tragedy with colleagues, I learned that many recalled only the horrific evidence broadcast during the inquest, depicting a young offender who committed suicide. This terminology tightly circumscribes and muffles the threat the narrative poses on our sense of justice and safety. Ashley’s mother, Coralee Smith, fought and won a trial concluding that Ashley did not take her own life -- it was brutally stolen from her. She also campaigned to protect her daughter’s memory, not as an offender, but as an individual who was barely out of childhood. Coralee Smith was, and remains, somebody’s mother.

This work aims to engage the viewer’s compassion and awareness that every life is precious and vulnerable. And everybody is somebody’s baby.

This show would not have been possible without Paul Petro Contemporary Art, Kim Pate (Canadian Association of Elizabeth Fry Societies), Dana Bingley, (catalog essay below) and Ashley Smith’s family.

Gretchen Sankey November 2015